February 26, 2012

About

1847 there arrived in San Francisco from Utica, upstate New York,

a man named Alfred J. Ellis. Ellis ran a saloon and a boarding

house on Montgomery Street. According to the lore of his present-day

family, he charged 50 cents for a blanket, filched his customers'

blankets as they slept, then charged $5.00 for "losing"

them.

About

1847 there arrived in San Francisco from Utica, upstate New York,

a man named Alfred J. Ellis. Ellis ran a saloon and a boarding

house on Montgomery Street. According to the lore of his present-day

family, he charged 50 cents for a blanket, filched his customers'

blankets as they slept, then charged $5.00 for "losing"

them.

(The boarding house here is a generic illustration from The

Annals of San Francisco, not Ellis's particularly, but Ellis's

was probably similar).

While the blanket story may be apocryphal, Ellis's name appears

multiple times in The Annals of San Francisco, published

1855 - there's a copy on the table - showing that he was prominent

in Gold Rush San Francisco.

In 1849 he served as a San Francisco delegate to the Constitutional

Convention, which met in Monterey in September and finished drafting

a state constitution in October.

Alfred

J. Ellis also served on San Francisco's ayuntamiento, or

town council, in 1849, along with other men whose names are memorialized

as San Francisco streets: Geary, Guerrero, Green, Brannan, Townsend,

and Post. Like those, Ellis's name is prominent today: Ellis Street,

named by surveyor Jasper O'Farrell in 1847, runs from Market and

5th Street North in downtown to St. Joseph's Avenue in the Western

Addition.

Alfred

J. Ellis also served on San Francisco's ayuntamiento, or

town council, in 1849, along with other men whose names are memorialized

as San Francisco streets: Geary, Guerrero, Green, Brannan, Townsend,

and Post. Like those, Ellis's name is prominent today: Ellis Street,

named by surveyor Jasper O'Farrell in 1847, runs from Market and

5th Street North in downtown to St. Joseph's Avenue in the Western

Addition.

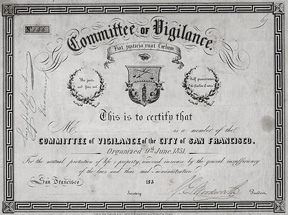

In 1851 Ellis was elected to the State Assembly. Besides public

office, Ellis also served in San Francisco's famous extra-legal

body the Committee of Vigilance." Along with the thousands

of gold-seekers who poured in to San Francisco were get-rich-quick

artists, swindlers, and desperate, violent criminals. The Annals

recorded:

In the spring and early summer months of 1849, San Francisco

was afflicted with the presence and excesses of…the veriest

rogues and ruffians that ever haunted a community… Long before

any great number of the general public had emigrated from the

Atlantic States or from Europe, San Francisco was overrun with

such men… Their baggage was on their backs, and their purse

in every honest man's pocket… These vagabonds never intended

to follow a reputable calling there, but as sharpers, gamblers,

and cheating adventurers in every variety of scheme, were prepared

only to prey upon the community at large.

Authorities were overwhelmed. Crime was open and brazen. More

criminals arrived from Australian penal colonies and congregated

in "Sydneytown" on the southwest slope of Telegraph

Hill. Events following the great fire of May 3, 1851, were the

last straw. District Court Judge Levi Parsons abolished the grand

jury, and dismissed charges against Benjamin Lewis, an Australian

being held for arson. On June 9, 1851, a group led by Samuel Brannan,

William T. Coleman, and others, formed the nucleus of what would

be called "Vigilantes." They signed a logbook and drafted

a constitution, which began.

WHEREAS, it has become apparent to the citizens of San Francisco,

that there is no security for life and property, either under

the regulations of society as it at present exists, or under the

law as now administered; Therefore, the citizens, whose names

are hereunto attached, do unite themselves into an association

for the maintenance of the peace and good order of society, and

the preservation of the lives and property of the citizens of

San Francisco, and do bind ourselves, each unto the other, to

do and perform every lawful act for the maintenance of law and

order and to sustain the laws when faithfully and properly administered;

but we are determined that no thief, burglar, incendiary or assassin,

shall escape punishment, either by the quibbles of the law, the

insecurity of prisons, the carelessness or corruption of the police,

or the laxity of those who pretend to administer justice.

Subsequent paragraphs provided for a meeting and deliberation

room, staffed "at all hours of the day and night" with

members on the alert for acts of violence. If such act justified

the interference of the committee, the committee should assemble

"for the purpose of taking such action as a majority of the

committee…shall determine upon."

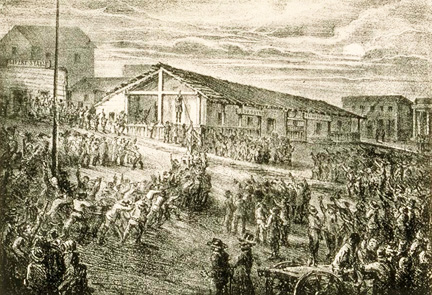

The Committee did not have long to wait. On the evening of June

10, 1851, a shipping agent named George Virgin left his office.

He had been stalked by a Londoner named Simpton, who had been

transported to Australia and had come to San Francisco. Simpton

had come to Virgin's office to case it. Virgin kept his receipts

in a safe, which was not too heavy to carry. Having moored a boat

at Long Wharf, Simpton waited some minutes after Virgin left the

office, then broke in with a chisel and put the safe in a heavy

canvas bag. But Virgin, remembering something he had forgotten

at the office, came back up the stairs as Simpton was coming down.

Seeing the door broken open and the safe gone, Virgin ran out

yelling "Stop Thief!"

At Long Wharf Simpton threw his burden onto the boat, cast off,

and began rowing towards Sydneytown. He was intercepted by a boatman

named Sullivan who had heard the ruckus on the wharf. As other

boats pulled alongside, Simpton threw the canvas bag overboard.

After being herded back ashore and beaten, he was taken by two

Vigilantes to the committee rooms on Battery Street near Pine.

Simpton's pursuers having seen him throw the bag with the safe

into the bay, it was brought up with hooks. About eighty members

having gathered, they deliberated whether to hand Simpton over

to the authorities, hold him, or try him, until a member said

"As I understand it, we came here to hang somebody."

A committee of the whole sat as court, Brannan presiding and a

member named Schenck prosecuting. The safe was produced in evidence

and Virgin testified. Simpton was arrogant and defiant, obviously

expecting to be let off like other "Sydney Ducks," as

they were called, or rescued by them. He hurt himself by saying

his name was "John Jenkins," an obvious alias.

After about two hours the committee voted unanimously for conviction

and execution. Simpton-Jenkins stayed arrogant. He asked for a

cigar and brandy, which were given him. About 1:00 a.m. Brannan

told the crowd that the prisoner would be taken to Portsmouth

Plaza and hanged. The crowd roared approval. After Jenkins arrogantly

dismissed the efforts of a clergyman to get him to repent, he

was led to the old customs house on the plaza. A few police tried

to interfere, but were forced back at gunpoint. A rope was thrown

over a projecting beam, the noose was put around the prisoner's

neck, and about 20 men pulled him up.

A coroner's jury concluded that Jenkins had died of strangulation

and implicated nine Committee of Vigilance members. The Vigilantes

responded with a resolution condemning the jury's "invidious

verdict" and for its singling out only nine names. The resolution

was unanimous, signed by 183 members, including Ellis. In effect

the Vigilantes were daring the authorities to take action against

them, which they didn't.

The Vigilantes disbanded in 1852, and reassembled in 1856 in response

to the shooting of Evening Bulletin editor James King.

The Second Committee of Vigilance, consisting of over 3,000 members,

was organized on military lines, with companies. Ellis served

as a company commander.

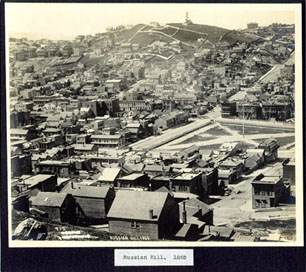

Ellis's

family remembers another story. Some residents of Ellis's boarding

house complained that his whiskey tasted bad. Ellis said the whiskey

was all right, and suggested the bad taste came from the well

water it was mixed with. In the well was found the dead body of

a Russian sailor. Ellis suggesting burying the dead man on a hill

behind his property; the hill was later known as Russian Hill.

It must be said however that Russian Hill may have gotten its

name from not one grave, but several.

Ellis's

family remembers another story. Some residents of Ellis's boarding

house complained that his whiskey tasted bad. Ellis said the whiskey

was all right, and suggested the bad taste came from the well

water it was mixed with. In the well was found the dead body of

a Russian sailor. Ellis suggesting burying the dead man on a hill

behind his property; the hill was later known as Russian Hill.

It must be said however that Russian Hill may have gotten its

name from not one grave, but several.

Russian ships had come to San Francisco since the beginning of

the 19th century, and legend has it that dead seamen and soldiers

had been buried on the hill from before San Francisco's founding,

hence the name Russian Hill.

In

any case, Ellis had a desirable property. Russian Hill - seen

here from Telegraph Hill in the 1860's - has picturesque views

of the Golden Gate, and is famous today for the Hyde Street Cable

Car, which crosses Lombard Street just west of the "Crookedest

Street in the World," a one-way block between Hyde and Leavenworth,

where cars tie up traffic for blocks for the distinction of driving

down it.

In

any case, Ellis had a desirable property. Russian Hill - seen

here from Telegraph Hill in the 1860's - has picturesque views

of the Golden Gate, and is famous today for the Hyde Street Cable

Car, which crosses Lombard Street just west of the "Crookedest

Street in the World," a one-way block between Hyde and Leavenworth,

where cars tie up traffic for blocks for the distinction of driving

down it.

Hyde Street Cable Car

Also according to family lore, Alfred J. brought his brother

Moses Charles Ellis out west (or possibly he induced him to come).

As early as 1852 the San Francisco City Directory lists Moses

Ellis as "Commission Merchant," Battery Street. The

brothers appeared in city directories through the 1850's.

Moses Charles prospered, growing and processing wheat, running

a steamboat line on the Sacramento River, establishing Santa Clara

County's first commercial fruit-drying operation the Sunnyvale

Fruit Drying Company, and incidentally fathering 17 children.

The San Francisco City Directory for 1887 lists the brothers as

flour merchants in Tehama County, their last entry.

A great-grandson of Moses Charles was Dr. Joseph Catton, a psychiatrist

and medical legal expert who testified in notable California criminal

trials. A son of Dr. Joseph was Moses Charles Ellis Catton - named

for his great-great grandfather.

In 1952 Ellis, as he was called, purchased a parcel off Magdalena

Avenue, Los Altos Hills, which had been part of the Hale Ranch,

which included the Thomas Wright carriage house. To finance the

purchase, Ellis Catton contacted a bank in Los Altos, which sent

out an elderly gentleman appraiser. He took one look and approved

a loan. The man was Mike Wright. "I was raised here,"

he said, tears in his eyes. His father was the Hale ranch caretaker,

Thomas Wright.

Ellis Catton converted the carriage house into today's family

home.

The

Entrance of the Catton House

The

Entrance of the Catton House

The floor, 21/2-inch thick redwood tongue and grooving. was removed

and put it in the ceiling, angled to give a cathedral effect.

Ellis removed a narrow stairway and groom's loft, replaced the

carriage door with a bay window, and converted the tack room to

a bedroom.

A horse stall was converted to a bathroom, with the original

window retained. There were no utilities at the original carriage

house. Water came from a stream, gas was bottled. Ellis eventually

had lines run in.

A dining room has a large fireplace, also added by Ellis. Much

of the lumber used came from the old Portuguese Dairy buildings

at the end of San Antonio Road.

Furnishings

are antique. A long oak dining table and chairs, bought by Ellis's

father, were made by a San Francisco cabinet maker. A sandalwood

and rosewood bedside table was made in 1838 by Moses Charles Ellis

in Utica, New York. It survived San Francisco's earthquake and

fire of April, 1906, and was owned by Moses Charles' niece Mary

Ellis. There is an 1854 English chess and gaming table, similar

to one given President Lincoln.

Furnishings

are antique. A long oak dining table and chairs, bought by Ellis's

father, were made by a San Francisco cabinet maker. A sandalwood

and rosewood bedside table was made in 1838 by Moses Charles Ellis

in Utica, New York. It survived San Francisco's earthquake and

fire of April, 1906, and was owned by Moses Charles' niece Mary

Ellis. There is an 1854 English chess and gaming table, similar

to one given President Lincoln.

The Catton House today is a link between California's storied

past, and its dynamic present.