It

can be a very difficult thing, to be the offspring of a famous

parent. When that parent is not just famous, but idolized as a

military hero who saved his country and is twice elected to the

highest office in the United States, that can define the offspring's

existence. So it would seem for Jesse Root Grant. Before we continue

with Jesse Root, however, let me recap his famous father's life.

It

can be a very difficult thing, to be the offspring of a famous

parent. When that parent is not just famous, but idolized as a

military hero who saved his country and is twice elected to the

highest office in the United States, that can define the offspring's

existence. So it would seem for Jesse Root Grant. Before we continue

with Jesse Root, however, let me recap his famous father's life.

Hiram Ulysses Grant was born in Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April

17, 1822, to Jesse Root Grant (the first one) and Hannah Simpson

Grant. The family moved to Ohio, where young Grant grew up on

a farm. With the nomination of his congressman, he entered the

United States Military Academy, West Point, in 1839. At the time

he was called by his middle name "Ulysses." The congressman

apparently thought that was young Grant's first name and added

his mother's maiden name Simpson to the application. It was easier

for Grant to change his name than change the paperwork, and he

became "Ulysses Simpson" - "U.S." for short.

He was not an especially distinguished student at West Point,

graduating 21st in a class of 39, although he was an excellent

horseman.

Ulysses Grant's parents, Jesse Root and Hannah Simpson Grant

When the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, Grant served

as a regimental quartermaster, and saw action. He was twice honored

for bravery. The war itself was begun by President Polk on a pretext

that Mexico had attacked first in Texas, which was never proved.

Grant in his memoirs - more of these later - regarded the war

"as one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against

a weaker nation. It was an instance of a republic following the

bad example of European monarchies…" It was typical

of Grant to express his conscience, but do what he saw as his

duty to his country.

The

war ended with the United States in possession of Texas, the Southwest,

and California.

The

war ended with the United States in possession of Texas, the Southwest,

and California.

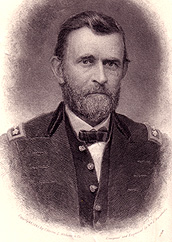

Ulysses Grant, 1846

In 1848 Grant married Julia Dent, the sister of a West Point classmate,

at her father's plantation near St. Louis, Missouri. Their first

son Frederick Dent Grant was born in 1850. In 1852 Julia was pregnant

with their second son Ulysses Jr., but the family was separated

when Grant was sent west by the army.

Coincidentally Grant was one of three army officers in California

in the 1850's who would become famous Union generals in the Civil

War a decade later: Grant, William T. Sherman, and Henry W. Halleck.

Sherman's and Grant's sojourns were not happy.

Sherman had resigned from the army to become a San Francisco banker

just as a recession started, and assumed responsibility as militia

commander against the Vigilantes of 1856 only to find he could

raise neither men nor arms. The experience gave him a permanent

dislike of politics.

Grant was stationed at various locations between the Washington

Territory and San Francisco, and sadly missed his wife and young

family. The separation from them may or may not have led him to

drink excessively, but in any case he got the reputation for it.

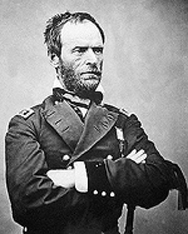

Pictures of the three suggest the differences between Sherman

and Grant on one hand and Halleck on the other: steely-eyed Sherman

shows ruthless determination; sad-eyed Grant also shows determination,

but a softer kind; wide-eyed Halleck is ill at ease, like an academic

- which Halleck was - befuddled by a question from a bright graduate

student.

William T. Sherman , Ulysses Grant, and Henry

W. Halleck

Ulysses Grant resigned from the army in 1854 and returned to

Julia. He worked a farm in Missouri, where their daughter Ellen

was born in 1855.

Happy

to be back with his family, Grant nonetheless seemed aimless.

He tried real estate in partnership with Julia's cousin, but had

no gift for business. In February, 1858 Julia bore their last

child, a son Jesse Root Grant, named after his grandfather.

Happy

to be back with his family, Grant nonetheless seemed aimless.

He tried real estate in partnership with Julia's cousin, but had

no gift for business. In February, 1858 Julia bore their last

child, a son Jesse Root Grant, named after his grandfather.

Frederick Dent Grant

Ulysses S. ("Buck") Grant, Jr.

Ellen ("Nellie") Grant

c. 1862

Jesse Root Grant, c. 1864

Ulysses Grant then took his family to Galena, Illinois and worked

in his father's leather store.

Grant might have lived out an obscure existence; but after the

election of avowed anti-slavery Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln

as president, Southern slaveholding states claimed that the federal

Union was dissolved.

In April, 1861, the so-called Confederate States fired on Fort

Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, South Carolina. The resulting

Civil War brought out dormant characteristics of Ulysses Grant.

When President Lincoln called for militia volunteers, Grant helped

recruit a company and took it to Lincoln's hometown Springfield,

Illinois. Requesting a field command, Grant was appointed militia

colonel by Illinois Governor Yates.

In August, 1861 he was appointed brigadier general of militia

(9) volunteers by President Lincoln; the first of many appointments

by him.

In August, 1861 he was appointed brigadier general of militia

(9) volunteers by President Lincoln; the first of many appointments

by him.

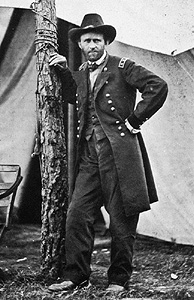

General Grant, 1863

Grant rapidly rose through the ranks of the Union Army. His reputation

for alcohol, made him enemies in the army, but he had President

Lincoln's complete confidence: "I can't spare this man; he

fights." Grant's capture of the crucial points of Fort Donelson

on the Cumberland River in Tennessee and Vicksburg, on the Mississippi

River were major Union victories in the west, and led to Lincoln

giving Grant command of the Army of the Potomac with the task

of destroying the army of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.

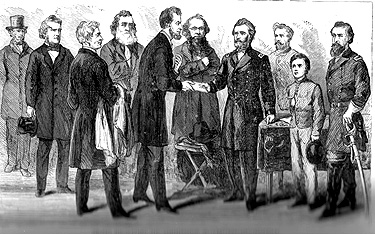

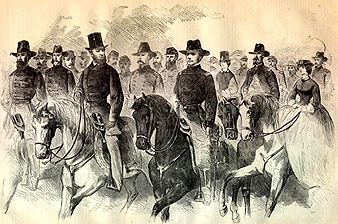

President Lincoln commissions Grant Lieutentant-General

Grant accepted the challenge, as always, with modesty and determination.

Lincoln said "General Grant is the most extraordinary man

in command that I know of. I heard nothing direct from him and

wrote to know why, and whether I could do anything to promote

his success. Grant replied that he had tried to do his best with

what he had; if he had more men and arms, he believed he could

accomplish more, but he supposed I had done and was doing all

I could." It was in complete contrast with previous Union

commanders who complained that they weren't being supported by

Lincoln. Other union commanders had superior troop numbers, but

never used them to advantage. Grant's strategy was basic: "To

hammer continuously against the armed force of the enemy until

by the mere attrition of the lesser with the larger body, the

former should be worn out."

In 1864 Grant besieged the Confederate Capital at Richmond, Virginia.

His headquarters were in City Point, Virginia, about a dozen miles

south of the city. During the Richmond campaign Grant's sons Frederick,

who had served as aide, and Ulysses Jr., and daughter Nellie were

at school in Burlington, New Jersey. Jesse Grant and his mother

Julia joined General Grant at City Point.

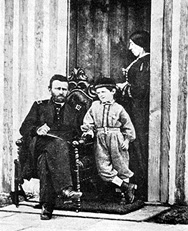

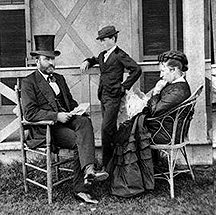

Grant,

Jesse Grant, Julia Grant at City Point, Virginia, 1864

Grant,

Jesse Grant, Julia Grant at City Point, Virginia, 1864

President Lincoln reviewing troops on horseback.

Aged under seven, Jesse was practically a front-line

witness to the Civil War. He recorded memories of it in 1925,

here in Los Altos.

City Point was then but a considerable plateau crowning

a steep bluff at the junction of the James and Appomattox rivers…

There father had established a supply base and had his headquarters…

log cabins…eight or ten of them in a row…occupied

as military headquarters… Father's cabin stood in the middle

of the row, and was slightly larger than the others.

And here, as I remember, I first met President Lincoln. Two

occasions, only, are impressed upon my memory…

President Lincoln, accompanied by Mrs. Lincoln and their youngest

son, Tad, then a year or two older and considerably larger than

I, came to City Point… (13) Father rode at the head of

his staff to the reviewing station, and at his side rode President

Lincoln. Mother, Mrs. Lincoln, Tad, and I, had preceded them

in an ambulance… the horse President Lincoln rode walked

calmly, almost as though conscious that his burden must be carried

with anxious care, while the President sat stiffly erect, the

reins hanging slack from his hands.

…I had always looked upon (father) as the largest…man

in the world. But beside President Lincoln father looked small,

and for the first time I saw him as a young man.

In a tightly buttoned frock coat, and wearing a high hat, Mr.

Lincoln appeared enormously tall, much taller than when standing.

And to me, the boy watching from the ambulance, the unsmiling,

worn, but kindly face, the tall flack-coated form, riding before

that colorful throng, gave a feeling of awe that time has not

effaced.

By March, 1865 Grant's army of 115,000 had surrounded Lee's 54,000

at Petersburg, south of Richmond. After a futile attack on Grant,

Lee slipped out of Petersburg in early April. The Confederate

capital fell, and Lincoln himself went there practically unguarded.

With characteristic tenacity Grant pursued Lee west. On Palm Sunday,

April 9th, Lee was boxed in by Grant behind and General Sheridan's

cavalry, plus two corps of infantry, in front.

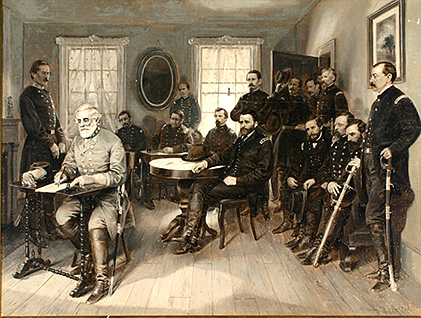

After an exchange of letters, Grant, Lee, and their staffs met

at a private home at Appomattox, Virginia. Grant telegrammed Lincoln

that Lee had surrendered his army on terms proposed by Grant.

Robert E. Lee, left, accepts Grant's terms

of surrender at Appomattox.

Five days later, Friday, April 14th - Good Friday - Grant was

in Washington. Jesse went to the White House with his father,

who conferred with Lincoln and others for some time. "I remember

that Mr. Lincoln smiled and spoke to me when we first came in,

and then he and father were immediately absorbed in earnest, low-voiced

talk while I wandered aimlessly about the room." Jesse got

bored and resentful that no one paid attention to him.

That evening Jesse and Julia were at the Willard Hotel preparing

to go to Burlington to see the Grants' other children. When General

Grant joined them for dinner he said something disappointing.

They would not go to Burlington that evening: President Lincoln

had invited General and Mrs. Grant to accompany himself and Mrs.

Mary Lincoln to Ford's Theatre to see the play Our American Cousin,

comedy starring popular actress Laura Keene; not great theatre,

but a diversion from their recent cares. Grant had conditionally

accepted. Word had gotten out, and Grant being an unfamiliar figure

in Washington, Washingtonians wanting to see him had bought out

all tickets and scalpers were getting two or three times tickets'

face value. Julia objected: she wanted to see her children in

Burlington, besides which she disliked Mrs. Lincoln.

Grant said he alone would go to the theatre, and go to Burlington

the next day. Jesse and Julia took a coach to the railway station.

What Jesse recorded next may have happened, or it may have been

a trick of memory over 60: as the coach rolled through Washington

D.C. a man rode alongside, peered in as though expecting to see

someone, then quickly rode away. At the railway station, Jesse

and Julia were surprised and happy to see General Grant, carrying

a bunch of papers. He did not attend the play. The Lincolns had

invited a young engaged couple of their acquaintance instead.

They changed trains at Baltimore. When they reached Philadelphia

a crowd was there, and surged about their railway car. A belligerent

brakeman was guarding the car, Jesse remembered, "from an

agitated deputation of state, city, and railway officials"

clamoring to get in. Grant admitted them, and heard that President

Lincoln had been shot at the theatre. The assassin John Wilkes

Booth had intended to kill both Lincoln and Grant.

Jesse stayed in Burlington, although he couldn't remember later

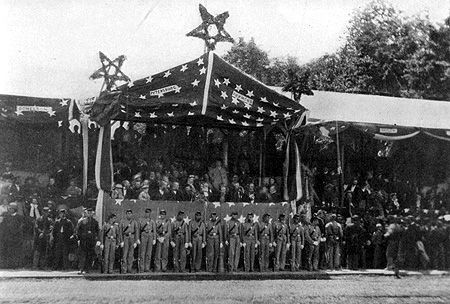

just how long. In May, 1865 there was a tremendous review in Washington

of the armies of Generals Sherman and Meade. Jesse, "wearing

a Scotch cap" - here - was on the stand with his father and

President Andrew Johnson, "leaning over the railing and much

interested." Marching soldiers hailed Grant, who was embarrassed

at such displays, and practically ignored Johnson.

General

Grant and family, c. 1865.

General

Grant and family, c. 1865.

The Grant family lived in Philadelphia for a time, moved to

Georgetown, D.C., then to a house on I Street in Washington. Jesse

got his first regular schooling, which he avoided every chance

he got, pleading sickness. Julia was stricter, but General Grant

was thoroughly indulgent with all his children and often took

Jesse to Army headquarters. Grant served briefly as Secretary

of War after President Johnson dismissed Secretary Edwin Stanton,

which Radical Republicans used as an excuse to impeach the hapless

Johnson. Impeachment failed of conviction by one vote in the Senate.

In 1868 the unpopular Johnson was not nominated for President

by the Republican Party. It turned to another candidate who was

sure to win: Ulysses S. Grant.

The Grants were still living on I Street when Grant was nominated

for the Presidency. Grant, said Jesse, made "absolutely no

effort to secure the nomination," but accepted it as another

duty he had to fulfill. He defeated the Democratic nominee, New

York Governor Horatio Seymour, but by a surprisingly small popular

vote margin, although he won easily in the Electoral College.

Just 46 in 1868, Grant was the youngest man ever elected to the

Presidency, a record that would stand until 43-year-old John Kennedy

was elected in 1960. We will not detail Grant's presidency here.

Suffice it to say that historians rate it as unsuccessful as his

earlier civilian life. He had never held elective office and had

no gift for politics. His two administrations, from 1869 to 1877,

with a few notable exceptions such as foreign affairs and the

15th Amendment, were corrupt and incompetent; not Grant himself,

but the cronies and opportunists who surrounded him.

President Ulysses S. Grant, Jesse, Julia, c.

1869

For Jesse the White House years were a notable change:

he had moved around all his short life, from Missouri to Ohio

and Illinois, and through Civil War campaigns. The eight years

in the White House were Jesse's longest period in the same home

his whole life until his nine to ten years in Los Altos Hills,

and even then he was not at the same address. He was unimpressed

with the White House initially: the carpets and furniture were

"dingy and shabby," until Julia installed new furnishings.

Jesse

treated the White House as his playground. He went to school,

"but not with great regularity."

Jesse

treated the White House as his playground. He went to school,

"but not with great regularity."

I gathered around me a new company of boys who lived in that

section of Washington and we became great friends. The White House

lot was our playground in good weather, and the big, airy basement,

or ground floor, was reserved for rain or storm. I never considered

that my position…entitled me to any special consideration,

and I know that no playmate ever accorded me deference because

of that fact. They flocked to the White House because there was

the largest and best playground available. And mine was the life

of an ordinary freckle-faced small boy in good health and fine

spirits, who adored his father and mother, his two brothers and

sister, and was in turn much loved and petted by them.

President Grant, family, a servant, and family

friend, c. 1870

In 1871 Jessie and his White House friends formed

a secret club, the K.F.R. One of the club's secrets was what the

initials stood for. President Grant thought they were an anagram

of "Kick, Fight, and Run." Jesse was elected first president.

The constitution stated that one of the club's aims should be

to "improve its members individually and collectively in

mental and moral culture and to encourage them in their attempts

towards literary and mental success." Notwithstanding these

noble aims, the club's minutes contained such entries as "With

great disorder the meeting then adjourned," and "That

a fine of ten cents be imposed upon all that are guilty of fraudulent

voting." The society published a journal, which would give

"vent to our extraordinary literary genius." The K.F.R.

continued active until 1883. Remarkably for a boys' club, its

members kept in touch and held annual reunions, all the way to

the 50th in 1921.

Please click Part 2

for continuation of the Jesse Root Grant presentation.

Part 2